INSIGHT by Gabriela Cugat, Economist, and Futoshi Narita, Senior Economist | Research Department of the International Monetary Fund. This insight was first published by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with the IMF Blog.

〉Emerging markets and developing economies are particularly vulnerable to the economic impact of COVID-19.

〉The pandemic threatens 20 years of progress and will likely lead to greater inequality, according to the latest World Economic Outlook by the IMF.

〉Investment in retraining and reskilling programs and relaxing eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance could help countries ease the devastation.

| Emerging markets and developing economies grew consistently in the two decades before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, allowing for much-needed gains in poverty reduction and life expectancy. The crisis now puts much of that progress at risk while further widening the gap between rich and poor.

Despite the pre-pandemic gains in poverty reduction and lifespans, many of these countries have struggled to reduce income inequality. At the same time, they saw persistently high shares of inactive youth (i.e., those not in employment, education, or training), wide inequality in education, and large gaps remaining in economic opportunities for women. COVID-19 is expected to make inequality even worse than past crises since measures to contain the pandemic have had disproportionate effects on vulnerable workers and women.

As part of our latest World Economic Outlook we explore two facts about the current pandemic to estimate its effect on inequality: a person’s ability to work from home and the drop in GDP expected for most countries in the world.

| The impact of where you work

First, the ability to work from home has been key during the pandemic. A recent IMF study shows that the ability to work from home is lower among low-income workers than for high-income earners. Based on data from the United States, we know that sectors with activities more likely to be performed from home saw a smaller reduction in employment. These two facts combined tell us that lower-income workers were less likely to be able to work from home and more likely to lose their jobs as a result of the pandemic, which would worsen the income distribution.

Second, we use the IMF’s GDP growth projections for 2020 as a proxy for what the aggregate decrease in income will be. We distribute this loss across income brackets in proportion to their ability to work from home. With this new income distribution, we compute a post-COVID summary measure of income distribution (Gini coefficient) for 2020 for 106 countries and compute the percent change. The higher the Gini coefficient, the greater the inequality, with high-income individuals receiving much larger percentages of the total income of the population.

What this tells us is the estimated effect from COVID-19 on the income distribution is much larger than that of past pandemics. It also provides evidence that the gains for emerging market economies and low-income developing countries achieved since the global financial crisis could be reversed. The analysis shows that the average Gini coefficient for emerging market and developing economies will rise to 42.7, which is comparable to the level in 2008. The impact would be larger for low-income developing countries despite slower progress since 2008.

| Welfare will suffer

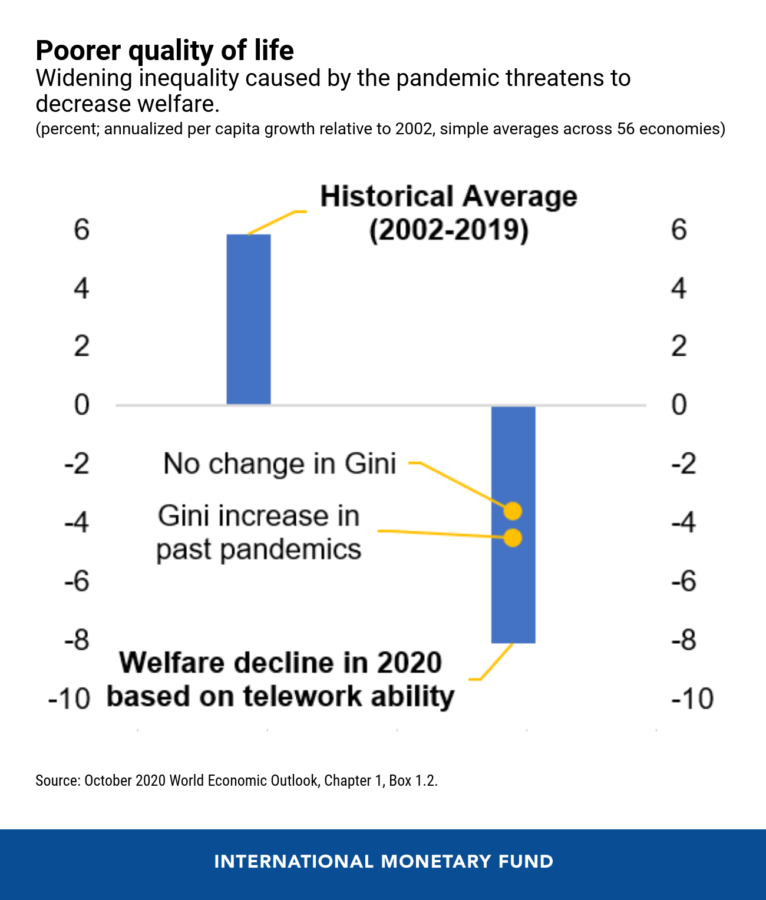

This widening inequality on average has a clear impact on people’s well-being. We assess the progress made before the pandemic and what we can expect for 2020 in terms of welfare using a measure that goes beyond GDP. We use a welfare measure that combines information on consumption growth, life expectancy, leisure time, and consumption inequality. Based on these measures, from 2002 to 2019, emerging markets and developing economies enjoyed welfare growth of almost 6 percent, which is 1.3 percentage points higher than per capita real GDP growth, suggesting many aspects of peoples’ lives were seeing improvement. The increase was mostly due to improvements in life expectancy.

The pandemic could reduce welfare by 8 percent in emerging markets and developing countries with more than half of it stemming from the excess change in inequality as a result of a person’s ability to work from home. Note that these estimates do not reflect any income redistribution measures after the pandemic. This means that countries can dampen the effect on inequality and on welfare more generally by policy actions.

| What can we do about it?

In our latest World Economic Outlook, we outlined some policies and measures to support affected people and firms that will be essential for keeping the inequality gap from widening further.

Investment in retraining and reskilling programs can boost reemployment prospects for adaptable workers whose job duties may see long-term changes as a result of the pandemic. Meanwhile, expanding access to the internet and promoting financial inclusion will be important for an increasingly digital world of work.

Relaxing eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance and extending paid family and sick leave can also cushion the impact the crisis is having on jobs. Social assistance in the form of conditional cash transfers, food stamps, and nutrition and medical benefits for low-income households must not be withdrawn prematurely.

Policies to prevent decades of hard-won gains from being lost will be critical to ensuring a more equitable and prosperous future beyond the crisis.

This blog draws on the work conducted under a research collaboration on macroeconomic policy in low-income countries supported by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the FCDO.