We need a clean energy revolution, and we need it now. But this transition from fossil fuels to renewables will need large supplies of critical metals such as cobalt, lithium, nickel, to name a few. Shortages of these critical minerals could raise the costs of clean energy technologies.

One obvious route is to mine more virgin material, but this comes with its own costs and potentially unintended consequences. Another solution commonly discussed is to recycle more and use the metals already in circulation. The complication is that we do not currently have enough metals in circulation, and even with recycling taken into consideration, mineral production is still forecasted to increase by nearly 500%. So how should we proceed?

A fully circular economy is much more than recycling; it is keeping materials at their highest value. It is time to look beyond circular materials. These three mindset changes can help reduce demand for critical metals.

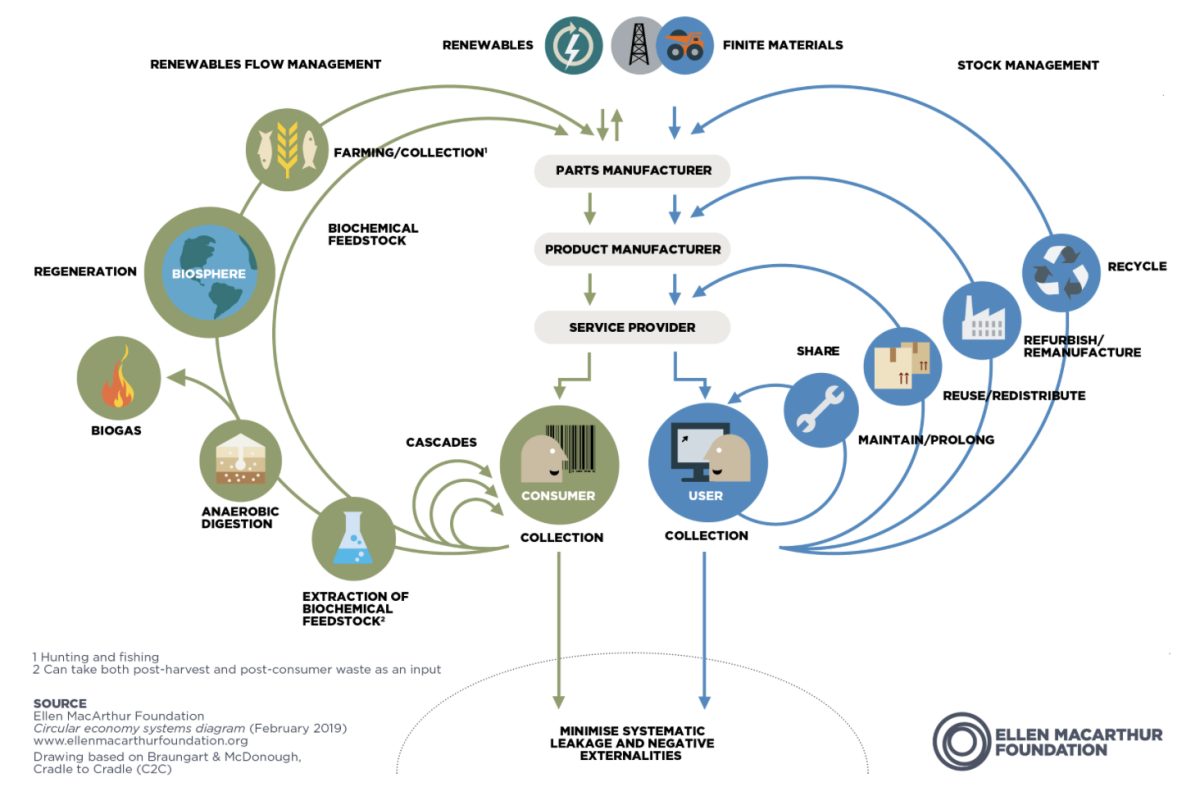

>> click to zoom in | On the circular economy system diagram by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, metals fall on the right-hand side of the diagram. This diagram shows a prioritization of approaches. The levers in the inner circles such as “maintain” and “remanufacturing” should be prioritized over those further outside, such as recycling. Source: Ellen McArthur Foundation.

>> click to zoom in | On the circular economy system diagram by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, metals fall on the right-hand side of the diagram. This diagram shows a prioritization of approaches. The levers in the inner circles such as “maintain” and “remanufacturing” should be prioritized over those further outside, such as recycling. Source: Ellen McArthur Foundation.

1. Go from owning to using

Be honest, you likely have at least one old mobile phone tucked in the bottom of a drawer. Possibly an unused hard drive taking up space too. You aren’t alone. The average car or van in England is driven just 4% of the time. While most already have a personal phone, 39% of workers globally have employer-provided laptops and mobile phones.

This is not at all resource efficient. More sharing can reduce ownership of idle equipment and thus material usage. Car sharing platforms such as Getaround and BlueSG have already seized that opportunity to offer vehicles where you pay per hour used.

To enable a broader transition from ownership to usership, the way we design things and systems need to change too. For example, car sharing is made possible by new keyless unlocking features. Similarly, user profiles that create a distinction for work and personal use on the same device is needed to reduce the number of devices per person. A design process that focuses on fulfilling the underlying need instead of designing for product purchasing is fundamental to this transition. This is the mindset needed to redesign cities to reduce private vehicles and other usages.

2. Enable preference for longevity

Who doesn’t want to get the most out of everyday products like washing machines, and increasingly domestic solar panels? Increasing a product’s longevity can reap significant dividends. Keeping a smart phone for five years instead of three reduces the phone’s annual carbon footprint by 31%.

The trouble is product companies are incentivized to sell more, not to design for longevity. While some product makers are transitioning to subscription models that reward longevity, a bigger opportunity lies with commerce platforms. Today, customers can search for products by price, brand, colour, technical specifications, and increasingly sustainability claims. Durability needs to become a feature too. Niche e-commerce site Buy Me Once offers only products that last for life. Their customers save both time and money, in addition to environmental benefits. However, more data and consistent durability metrics are needed before we can easily compare and choose durable products.

3. Build pride in second life

What if something can no longer be used for the purpose it was originally sold for? When an electric vehicle battery is replaced, it may still have up to 80% capacity remaining. Already, retired electric vehicle batteries have been repurposed to power streetlights and a stadium. General Motors is beginning to design batteries with the ease of transition to a second life in mind. Refurbished consumer electronics are slowly coming into fashion with start-ups such as Back Market and Refurbed.

In the business-to-business world, increasing lifespan by remanufacturing brings the added value of reducing cost and delivery time. Remanufacturing constitutes more in-depth work that restores used equipment to its original performance level. For large-scale investments, such as wind turbines, it can almost double the return on original investment by extending the turbine life by up to 20 years.

Introducing more of these circular models require significant effort and changes to our current way of life. Yet unless we can reduce metal demand quickly, we will need more new mines. Mining has been called the “blind spot” of the green energy transition. On land, it has been associated with biodiversity loss, overuse of water resources, tailings waste, labour and geopolitical issues. Interest is emerging to get these minerals from the deep-sea, but this is not without other environmental risks. If mining begins there, species not yet discovered by science could go extinct. Over 100 organizations and more than 600 experts are cautioning against doing so.

Much of the debate around opening new mines is shaped around supply and demand. A 2022 World Economic Forum white paper identified the question, “do we need these minerals?” as one of the knowledge gaps that need to be filled before a decision could be made on deep-sea mineral stewardship.

This transition to a fully circular model is now more urgent than ever. If we are to move forward, we need to reconsider at a systemic level how much we use, as well as how we can reduce usage. Unless we can dramatically reduce current metal usage, the debate and tension on finding new mines will not go away.

| All opinions expressed are those of the author and/or quoted sources. investESG.eu is an independent and neutral platform dedicated to generating debate around ESG investing topics.

Manganese nodule with a deep-sea sponge. MiningImpact Expedition SO242. Source: ROV KIEL6000, GEOMAR.

Manganese nodule with a deep-sea sponge. MiningImpact Expedition SO242. Source: ROV KIEL6000, GEOMAR.